Chapter 17: Impressionism

Portions of the following text are taken from smarthistory.org, which is available for use under CC BY-NC-SA. Please see the citations at the bottom of the page for more information. The text has been adapted to more closely adhere to Chicago Manual of Style and Ensign College Style Guide.

The group of artists who became known as the impressionists did something ground-breaking in addition to painting their sketchy, light-filled canvases: they established their own exhibition. This may not seem like much in an era like ours, when art galleries are everywhere in major cities, but in Paris at this time, there was one official, state-sponsored exhibition—called the Salon—and very few art galleries devoted to the work of living artists. For most of the 19th century, the Salon was the only way to exhibit your work (and, therefore, the only way to establish your reputation and make a living as an artist). The works exhibited at the Salon were chosen by a jury—which could often be quite arbitrary. The artists we know today as impressionists—Claude Monet, August Renoir, Edgar Degas, Berthe Morisot, Alfred Sisley (and several others)—could not afford to wait for France to accept their work. They all had experienced rejection by the Salon jury in recent years and felt that waiting an entire year between exhibitions was too long. They needed to show their work, and they wanted to sell it.

The artists pooled their money, rented a studio that belonged to the photographer Nadar, and set a date for their first collective exhibition. They called themselves the Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, and Printmakers, and their first show opened at about the same time as the annual Salon in May 1874. The impressionists held eight exhibitions from 1874 through 1886.

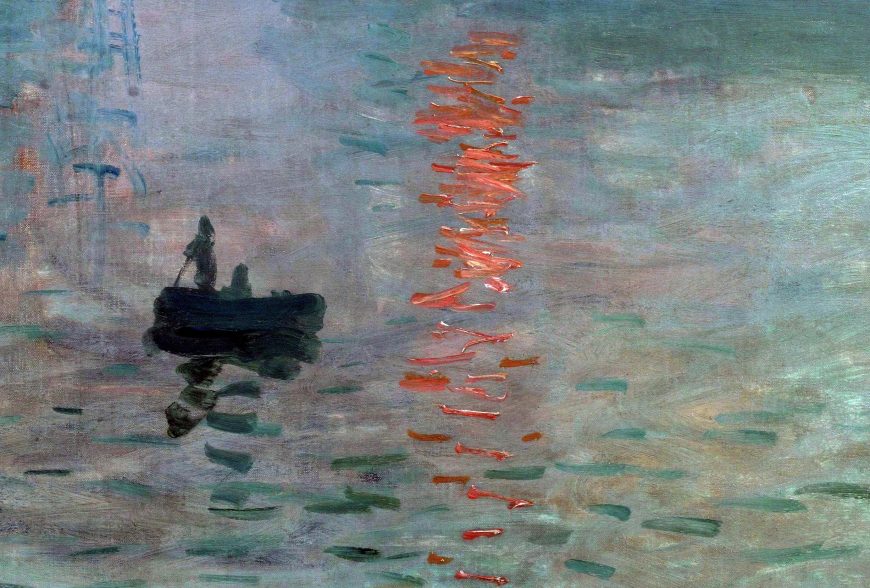

Claude Monet’s Impression: Sunrise is an exemplary impressionist painting in several ways, not least of which is its title. It depicts a misty harbor scene at Le Havre (a port city in Northern France) in which boats and figures are reduced to flat, shadowy silhouettes, while the red light of the sun reflected on the water takes on tangible form in highly visible brushstrokes.

What we see when we look at the painting is unquestionably painted; Monet made no effort to develop his suggestive image into a more detailed and finished rendering of the scene. The loosely sketched silhouettes of boats exemplify the difficulty of seeing objects in the mist with the sun rising behind them. Monet embraced this difficulty, using it as an occasion to display a painterly rendering that says more about the momentary light and atmospheric conditions than it does about the objects in the scene.

Ask yourself: is there anything in the painting that tells you this is Le Havre? In an interview, Monet acknowledged the failure of the painting to depict a recognizable place. When asked for the title of the painting for the catalog of what later became known as the first Impressionist Exhibition, he said: “I couldn’t very well call it a view of Le Havre. So I said: ‘Put Impression.'” With this decision, Monet unwittingly named an art movement, and this work’s emphasis on brushwork, light, and atmosphere at the expense of the clear representation of objects became a hallmark of the impressionist style.

Lack of finish

Monet, Renoir, Degas, and Sisley had met through classes. Berthe Morisot was a friend of both Degas and Manet (she would marry Édouard Manet’s brother Eugène by the end of 1874). She had been accepted to the Salon, but her work had become more experimental since then. Degas invited Morisot to join their risky effort. The first exhibition did not repay the artists monetarily, but it did draw critics, some of whom decided their art was abominable. What they saw wasn’t finished in their eyes; these were mere “impressions.” This was not a compliment.

The paintings of neoclassical and Romantic artists had a finished appearance. The impressionists’ completed works looked like sketches, fast and preliminary “impressions” that artists would dash off to preserve an idea of what to paint more carefully at a later date. Normally, an artist’s “impressions” were not meant to be sold, but were meant to be aids for the memory—to take these ideas back to the studio for the masterpiece on canvas. The critics thought it was absurd to sell paintings that looked like slap-dash impressions and to present these paintings as finished works.

We're at the Musée d'Orsay, and we're looking at a painting by Berthe Morisot, The Cradle.

This is a lovely painting of a baby in a cradle, being watched over by her new mother.

Her later work is some of the most radical painting in its extraordinary brushwork. But this is an early canvas.

This was exhibited at the Impressionist Exhibition of 1874. This is an exhibition of the artists whom we now call the impressionists, where they exhibited independently from the official art exhibitions in Paris. But sadly, this painting was little-noticed by the press and the public, and remained unsold for several years, and in the family until 1930.

It was extremely difficult to be a female painter at this time, and so it's not surprising that her work received little critical attention. There were some female painters that were successful. I'm thinking about Rosa Bonheur, for example. But, for the most part, especially women of Morisot's class, a woman of her level of affluence would have a quite restricted environment in which they could freely move. Women were expected to largely exist in the domestic sphere.

And, as we see in the work of so many women artists at the end of the 19th century, a lack of access to the more typical subjects of modern life, of cafés and bars. This was the space that they had access to, and that's what they painted. And Morisot would go on to paint many beautiful scenes of family life, but this one is especially poignant.

What we're seeing is Morisot's sister, looking over her daughter, and there's a wonderful intimacy. The child is angelic, draped under that gauzy net. And Morisot's sister looks down at her with a gentle concern that is really moving and beautiful.

It recalls for me images of Mary, holding the Christ child. But, in those cases, Mary holds the Christ child on her lap. Here we have a very modern domestic setting, with a cradle and a lovely interior in the background, with the curtain. And we have a sense of a modern woman in modern dress. Her lowered eyelids, the chin that rests on the hand. The other arm that comes forward, foreshortened across the cradle, suggests a contemplation about the serious responsibilities of motherhood, but also the incredible affection of motherhood.

The fact that this is seen worthy as a subject for a painting, is also a reflection of the growth of the idea of the middle-class family in the 19th century. That the domestic space was a protected space, an insular space.

And I think we see that here. Not only is the child enveloped in that gauzy material, but Morisot's sister herself is enclosed. On one side of her, she has the diagonal of that gauze. Above, another diagonal, formed by the curtain. And, to the left, the edge of the painting. So, she is also rather locked into this domestic space.

I wanna spend just a moment looking at the brushwork. Although there are some fine linear passages that are almost drawn, for instance, the fine locks of hair that fall down the woman's temple. Much of the brushwork is quite loose and anticipates Morisot's later style. Look, for example, at the pink fringe, at the edge of the netting. Or the way in which the collar of the woman is rendered. There's a beautiful looseness here that shows Morisot's extraordinary facility with paint.

Virtuosity is what comes to mind when I think of Morisot and the handling of paint. I notice it also in the white touches of paint that form the top of the curtain. Or even in her sleeve, those quick circular movements of paint, that suggest the texture of her dress.

And then there's choices that Morisot makes in terms of where our attention is going to fall. Look at the way in which the woman's fingers are painted so flatly. The upper parts of the fingers, which are foreshortened, are virtually not articulated at all. All that she's chosen to give us is the flat plains of the fingers, that are exposed directly to us.

I love those fingers, their slight sense of fidgetiness. Unfortunately, I think we still have a tendency to discount images of mothers and children, to see them nostalgically and sentimentally.

And, if we look around the galleries of the d'Orsay, almost every painting is by a man. Morisot is an exception. And, if we look at auction prices, if we look at the art market, female artists are still not given their due.

Landscape and contemporary life

Courbet, Manet, and the impressionists also challenged the Academy’s category codes. The Academy deemed that only “history painting” was great painting. These young realists and impressionists questioned the long-established hierarchy of subject matter. They believed that landscapes and genre scenes (scenes of contemporary life) were worthy and important.

In their landscapes and genre scenes, the impressionists tried to arrest a particular moment in time by pinpointing specific atmospheric conditions—light flickering on water, moving clouds, a burst of rain. Their technique tried to capture what they saw. They painted small commas of pure color one next to another. When the viewer stood at a reasonable distance, their eyes would see a mix of individual marks: colors that had blended optically. This method created more vibrant colors than colors mixed as physical paint on a palette.

An important aspect of the impressionist painting was the appearance of quickly shifting light on the surface of forms and the representation changing atmospheric conditions. The impressionists wanted to create an art that was modern by capturing the rapid pace of contemporary life and the fleeting conditions of light. They painted outdoors (en plein air) to capture the appearance of the light as it flickered and faded while they worked.

Tier 3: Concept—Impressionism

Learning to look and think deeply about artwork ultimately shows you how to reveal the concept or meaning that the work transmits. This is a highly subjective, but nonetheless very meaningful, interaction between the work and the viewer. As you consider this work, refer to the elements of art listed in Tier 3: Concept.

As a movement, impressionism begins in the spirit of reformation and revolution. Thus, the meaning of these pieces has changed throughout the years in connection with their reception, the general acceptance or rejection of a work or works by audiences.

By the 1880s, the impressionists accepted the name the critics gave them, though their reception in France did not improve quickly. Other artists, such as Mary Cassatt, recognized the value of the impressionist movement and were invited to join. American and other non-French collectors purchased numerous works by the impressionists. Today, a large share of impressionist work remains outside French collections.

It may be surprising to know that an art movement so well-loved today—highly successful at auction, the subject of numerous blockbuster exhibits, and a vast number of popular publications—was subjected to a good deal of scorn and ridicule in its early years. Even the term impressionism was first used pejoratively in relation to the new art first exhibited in 1874 by the Société anonyme cooperative d’artistes peintres, sculpteurs, etc. (Anonymous Society of Artists, Painters, Sculptors, etc.). These artists used the term “anonymous” quite intentionally—they wanted to avoid imposing a restrictive label or common agenda on their group, whose members employed a variety of styles and painting techniques. Ultimately, they staged eight exhibitions between 1874 and 1886.

The group included a number of artists who became the most famous impressionists: Gustave Caillebotte, Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro, Pierre Renoir, and Alfred Sisley, as well as many other artists (some of whom are now associated with later modern art movements such as postimpressionism or symbolism). Despite their eclecticism, contemporary viewers and the critics who reviewed the Société anonyme’s exhibitions expected the group to share common goals and characteristics, and the label impressionism soon came to identify a new artistic movement, with some of the artists of the Société anonyme at its core.

The critic Louis Leroy was the first to emphasize the term impression in relation to the new painting, adopting it from Monet’s Impression: Sunrise in a satirical dialogue entitled “Exhibition of the Impressionists” that was published in the popular illustrated magazine Le Charivari. Leroy found Monet’s use of “Impression” in his painting’s title particularly appropriate because it suggested that the work was unfinished according to Academic conventions of representation; that is, it represented a mere impression of the scene, rather than a fully structured and completed work of art. Leroy repeatedly emphasized the term impression in the dialogue and described many of the paintings by Monet and his fellow exhibitors as sloppy and slapdash, going so far as to compare Monet’s Impression: Sunrise to embryonic wallpaper and Pissarro’s Hoarfrost to paint scraped off of a dirty palette.

Despite this prominent early critical association of the term impression with sloppiness, two years later, impressionism and impressionist were being widely used to label the new art by its supporters as well as its detractors. It was undoubtedly the flexibility of the term that allowed it to be so widely adopted, but with that flexibility came a certain amount of confusion about the aims of the movement.

Leroy’s usage suggests a hasty and inaccurate “first impression,” but the term also has a very precise and technical connotation as a scientific word designating the stimulation of the optical or other sensory nerves. This scientific definition implies a project of careful observation and objective documentation, but the term is also used for a more subjective and individual response, as when one gives one’s own impressions of a person, place, or thing. Hasty generalization or precise observation? Objective documentation or subjective interpretation? All of these contradictory qualities have been associated with the impressionist movement.

Paris Street; Rainy Day, Caillebotte

The complex significance of impressionism expands further when we examine the characteristics emphasized in scholarly and popular writings about the movement. Two quite different artistic projects and sets of characteristics are commonly associated with impressionism:

First, a painting is considered impressionist if it exhibits a certain style, consisting of patchy brushwork and a light pastel color scheme that aims to capture transient effects of atmospheric lighting, as can be seen in Sisley’s Autumn: Banks of the Seine near Bougival.

Second, a painting is considered impressionist if it exhibits a certain type of subject matter, typically plein-air (painted out-of-doors) scenes of middle-class men and women at leisure: drinking in cafés, boating, swimming, attending horse races, promenading in gardens, and similar activities.

However, not all of the artworks shown by members of the Société anonyme exhibit both of these characteristics; in fact, some exhibited neither. The works of Camille Pissarro are typically in the impressionist style, but as his painting Hoarfrost indicates, he frequently painted the working class at labor rather than the middle classes at leisure. Edgar Degas and Gustave Caillebotte frequently painted the middle classes at leisure but did not employ the characteristic impressionist style.

When Caillebotte's, Paris Street, Rainy Day was exhibited in 1877 at the Impressionist Exhibition, one anonymous reviewer wrote, "Caillebotte is an impressionist in name only. He knows how to draw, and paints more seriously than his friends."

Well, you know, when we think of impressionism, we think of the countryside, light-filled summer, loose brushwork, and Caillebotte has given us this complex image of the subtlety of light in the city after a rainstorm. And without all of that loose, open brushwork. This reviewer is saying he knows how to draw. There is a sense of line, of contours, of forms that exist three-dimensionally in space. That's not what the impressionists were doing in 1877.

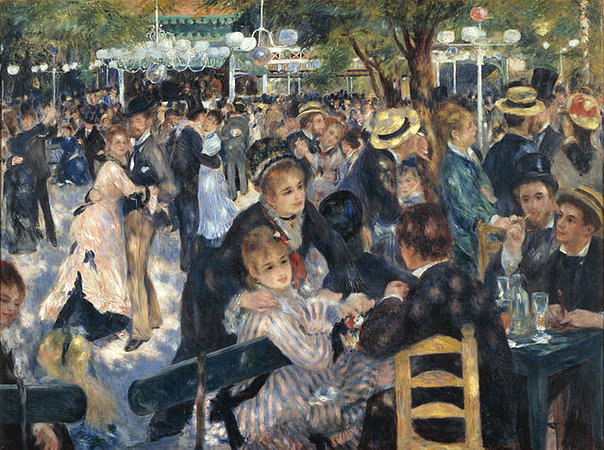

At that same exhibition, one could have seen Renoir's Moulin de la Galette.

Which is full of light and movement and open brushwork.

Or, paintings by Monet of the Gare Saint-Lazare, where Monet concentrated on the effects of light through the steam in that railway station.

In fact, so much so that even the massiveness of the locomotive dissolved within that atmosphere, but here Caillebotte has given us a sense of massiveness. Look at the apartment buildings in the background. Look at the cobblestones. These are solid forms.

Right. Nothing's dissolving into brushwork or light here.

And yet this painting is still all about light, but it's about its reflectivity. It's about shadow, and it's about the way that light can define forms in a far more solid way.

Caillebotte is painting modern Paris, wide boulevards that had just recently been built, and the modern apartment houses that lined those boulevards.

He's also giving us the middle class that then populated this city. Look at how fashionably dressed the couple in the foreground are.

Although, we do seem to have some different types of people. If we look closely, we mostly see those fashionable, upper-class or upper-middle-class people, but behind the woman to the right, just above her shoulder, we see someone who looks working class, and in the background, we see what looks like a painter carrying a ladder.

And, in fact, that was really one of the definitions of the new modern city, was the way in which the lives of people of different classes crossed on the streets. This is a painting that really is about intersections.

The rainy day, the yellowish-gray of the sky capturing a specific moment. Look at the sense of the reflectivity of the water between the cobblestones. This seems so spontaneous, as if this is this fragment of time, this moment. Nobody seems to be posed. The main figures aren't in the middle. Instead, the man on the right is actually cut off! We only see half his body. This would have been an aesthetic that would have felt very much at odds with classical art, and perhaps even would have been seen as coming out of the new vision of the photograph.

These are all things that would have felt very radical to an audience in 1877.

And yet, although we don't notice it at first, the painting is really carefully balanced, and carefully composed. This is not a snapshot. If we look at the painting, it's divided into four quadrants. You've got that vertical division in the middle of the canvas. Then, right at the level of the woman's mouth, moving across, and then at the bottom of the apartment in the background. They've got a painting that was divided into four areas, and there really is a sense of stability and balance, even though it's still asymmetrical. For all the seriousness of the issues that we're talking about, this is a really playful painting. For instance, look at the man who's clearly in the middle ground, but seems to be hopping off the red wheels of that coach that we see in the background. There are these playful juxtapositions that Caillebotte is very intentionally placing in here that speaks to the way in which the modern world has become a complex jumble, the way in which things come together in relationships that are unexpected.

And fragmentary and ephemeral, and these were all things that felt very modern in the 1870s. But he's having fun with them. Look, for instance, at the legs that are dangling from the umbrella held by the man in the center of the painting.

So Caillebotte continued to paint urban themes, though he died rather young when he was in his 40s, and he was independently wealthy, and so had no need to sell his paintings. Throughout his life, he collected the work of his friends of the impressionists, and amassed, actually, a really remarkable collection that he left to the French state. And his collection forms the heart of the great works that we see today at the Musée d'Orsay in Paris.

Questions to Consider

- In what ways was Caillebotte an impressionistic painter? In what ways is he not?

- What features of this painting inspired criticism from opponents of the impressionist cause?

This terminological confusion has led some historians to wish to discard the term impressionism altogether, but whatever label or labels are attached to them, these two projects—capturing the evanescent effects of atmospheric lighting, and depicting scenes of contemporary middle-class leisure—were significant artistic tendencies in Paris and, slightly later, in the wider Euro-American scene starting in the 1860s and 70s. Rather than attempt to limit the definition of the impressionist project, we embrace the flexibility of the term.