Chapter 5: Etruria and Ancient Rome

Portions of the following text are taken from smarthistory.org, which is available for use under CC BY-NC-SA. Please see the citations at the bottom of the page for more information. The text has been adapted to more closely adhere to Chicago Manual of Style and Ensign College Style Guide.

Before the small village of Rome became Rome, the great capital city and empire, a brilliant civilization controlled almost the entire peninsula we now call Italy. This was the Etruscan civilization, a vanished culture whose achievements set the stage not only for the development of ancient Roman art and culture but for the Italian Renaissance as well.

Though you may not have heard of them, the Etruscans were the first “superpower” of the western Mediterranean who, alongside the Greeks, developed the earliest true cities in Europe. They were so successful, in fact, that the most important cities in modern Tuscany (Florence, Pisa, and Siena, to name a few) were first established by the Etruscans and have been continuously inhabited since then.

Yet the labels “mysterious” or “enigmatic” are often attached to the Etruscans, since none of their own histories or literature survives. This is particularly ironic as it was the Etruscans who were responsible for teaching the Romans the alphabet and for spreading literacy throughout the Italian peninsula.

Etruscan influence on ancient Roman culture was profound. It was from the Etruscans that the Romans inherited many of their own cultural and artistic traditions, from the spectacle of gladiatorial combat to hydraulic engineering, temple design, and religious ritual, among many other things. In fact, hundreds of years after the Etruscans had been conquered by the Romans and absorbed into their empire, the Romans still maintained an Etruscan priesthood in Rome (which they thought necessary to consult when under attack from invading “barbarians”).

Legend has it that Rome was founded in 753 BCE by Romulus, its first king. In 509 BCE, Rome became a republic ruled by the Senate (wealthy landowners and elders) and the Roman people. During the 450 years of the Republic, Rome conquered the rest of Italy and then expanded into France, Spain, Turkey, North Africa, and Greece.

Rome became very Greek-influenced or “Hellenized,” and the city was filled with Greek architecture, literature, statues, wall paintings, mosaics, pottery, and glass. But with Greek culture came Greek gold, and generals and senators fought over this new wealth. The Republic collapsed in civil war and the Roman Empire began.

Etruscan Art

The Etruscan civilization was a major power in the Mediterranean before the formation of the Roman Empire. They settled the Italian peninsula, where several of their major cities have been continuously inhabited since. Although they were eventually absorbed into the Roman empire, the Etruscans had a significant impact on the art, religion, and culture of Ancient Rome. Early Rome was even ruled by a series of Etruscan kings. The Etruscans traded throughout the Mediterranean and were in contact with the Greeks. As a result, Etruscan art was heavily influenced by Greek art and is grouped into the same artistic periods as Greek art is. Although the Romans inherited the Etruscan alphabet, none of their own histories or literature have survived. Much of what we know about Etruscan culture and beliefs comes from their burials.

Roman Art

According to the Romans' own history, Rome was founded by Romulus in 753 BCE. However, the archaeological timeline indicates the area had already been inhabited for about 250 years prior. Rome began as a group of villages in the Capitoline Hills of Italy and grew to encompass the Mediterranean and beyond, becoming one of the largest empires the world has seen. The Romans were master engineers who specialized in creating large public structures. The development of concrete, vaulting, arches, and domes enabled them to create structures with large interior spaces. Roman buildings are characterized by having richly decorated interiors. The art of the republican era was defined by the use of verism, a hyper-realistic style that highlighted rather than concealed flaws and imperfections. Emphasizing the imperfections associated with old age was seen as a reference to the wisdom and intelligence that comes with aging and experience. Roman art and architecture were heavily influenced by Greek art and architecture; by the time the imperial age began, Roman art adapted the idealization of classical Greek art.

Ancient Roman Art

Roman art is a very broad topic, spanning almost 1,000 years and three continents, from Europe to Africa to Asia. The first Roman art can be dated back to 509 BCE, with the legendary founding of the Roman Republic, and the culture lasted until 330 CE (or much longer if you include Byzantine art). Roman art also encompasses a broad spectrum of media, including marble, painting, mosaic, gems, silver, bronze work, and terracottas, just to name a few. The city of Rome was a melting pot, and the Romans had no qualms about adapting artistic influences from the other Mediterranean cultures that surrounded and preceded them. For this reason, it is common to see Greek, Etruscan, and Egyptian influences throughout Roman art. This is not to say that all of Roman art is derivative, though, and one of the challenges for specialists is to define what is “Roman” about Roman art.

The Romans did not believe, as we do today, that to have a copy of an artwork was of any less value than to have the original. The copies, however, were more often variations rather than direct copies, and they had small changes made to them. The variations could be made with humor, taking the serious and somber element of Greek art and turning it on its head. For example, a famously gruesome Hellenistic sculpture of the satyr Marsyas being flayed was converted in a Roman dining room to a knife handle (currently in the National Archaeological Museum in Perugia). A knife was the very element that would have been used to flay the poor satyr, demonstrating not only the owner’s knowledge of Greek mythology and important statuary but also a dark sense of humor. From the direct reporting of the Greeks to the utilitarian and humorous luxury item of a Roman enthusiast, Marsyas made quite the journey. But the Roman artist was not simply copying. He was also adapting in a conscious and brilliant way. It is precisely this ability to adapt, convert, combine elements, and add a touch of humor that makes Roman art unique.

Typically the history of Rome is divided into two major periods: the Republic and the Empire. During the period of the Republic, Rome celebrated its democratic and philosophical ideals, evidenced by the stylistic choices of artisans of this time. In the Empire, Rome recast its identity as an heir of a divine right to rule, self-consciously connecting their history to that of the Greeks through myth and art.

The Roman Republic

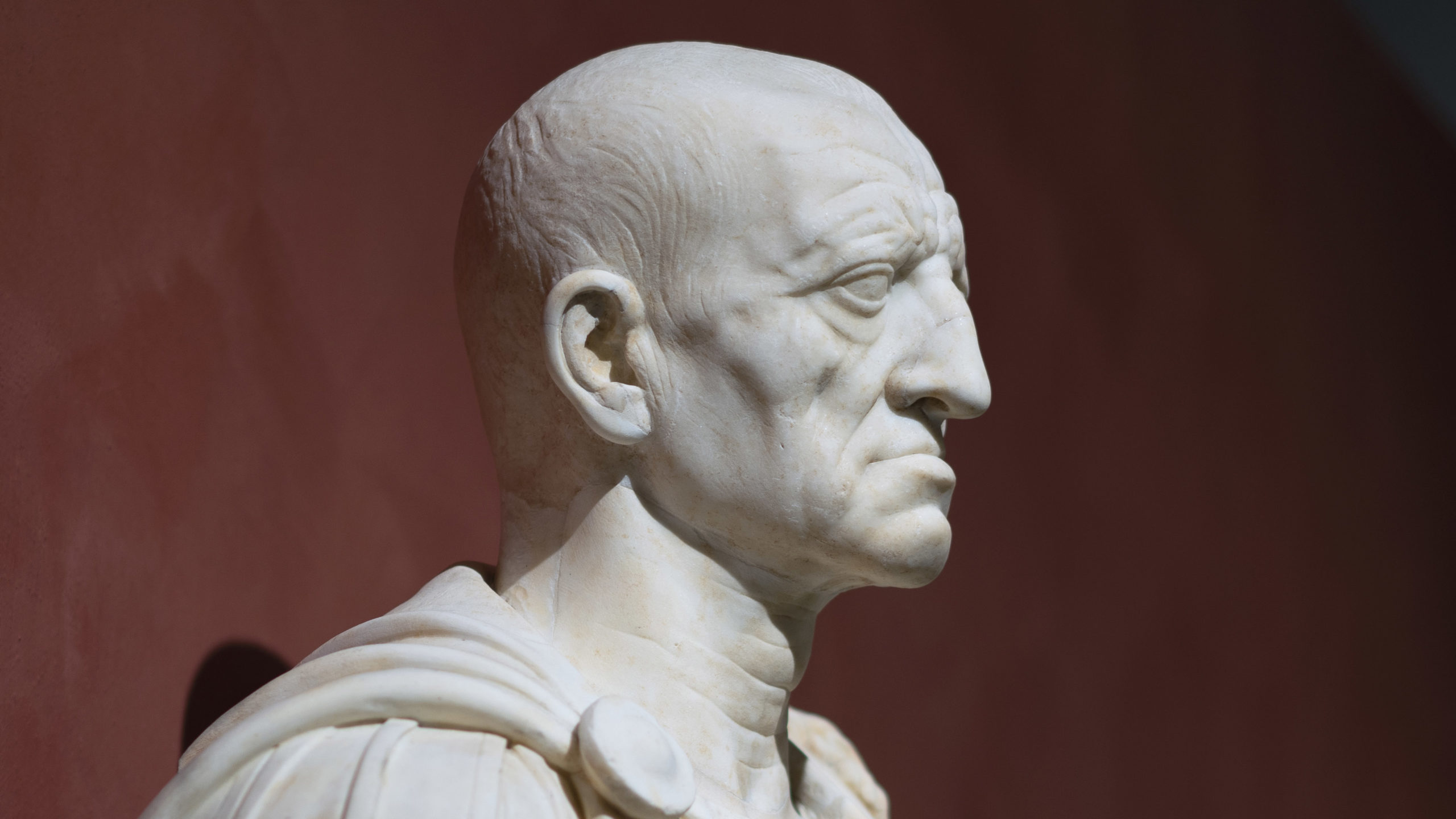

Seemingly wrinkled and toothless, with sagging jowls, the face of a Roman aristocrat stares at us across the ages. In the aesthetic parlance of the late Roman Republic, the physical traits of this portrait image are meant to convey the seriousness of mind (gravitas) and the virtue (virtus) of a public career by demonstrating how the subject literally wears the marks of his endeavors. While this representational strategy might seem unusual in the post-modern world, in the waning days of the Roman Republic it was an effective means of competing in an ever more complex socio-political arena.

The Head of a Roman Patrician

This portrait head, now housed in the Palazzo Torlonia in Rome, Italy, comes from Otricoli (ancient Ocriculum) and dates to the middle of the first century BCE. The name of the individual depicted is now unknown, but the portrait is a powerful representation of a male aristocrat with a hooked nose and strong cheekbones. The figure is frontal without any hint of dynamism or emotion—this sets the portrait apart from some of its near contemporaries. The portrait head is characterized by deep wrinkles, a furrowed brow, and generally an appearance of sagging, sunken skin—all indicative of the veristic style of Roman portraiture.

Questions to Consider

- Why did the artist choose to naturalistically depict even the flaws of this subject (such as wrinkles and protruding jaw)? Why not produce a work that was more flattering?

- What elements of art are evident to support the claim that this portrait reflects the aesthetic of Republican Rome?

Verism can be defined as a sort of hyperrealism in sculpture where the naturally occurring features of the subject are exaggerated, often to the point of absurdity. In the case of Roman Republican portraiture, middle-aged males adopt veristic tendencies in their portraiture to such an extent that they appear to be extremely aged and careworn. This stylistic tendency is influenced both by the tradition of ancestral imagines as well as a deep-seated respect for family, tradition, and ancestry. The imagines were essentially death masks of notable ancestors that were kept and displayed by the family. In the case of aristocratic families, these wax masks were used at subsequent funerals so that an actor might portray the deceased ancestors in a sort of familial parade. The ancestor cult, in turn, influenced a deep connection to family. For late Republican politicians without any famous ancestors (a group famously known as "new men" or homines novi) the need was even more acute—and verism rode to the rescue. The adoption of such an austere and wizened visage was a tactic to lend familial gravitas to families who had none—and thus (hopefully) increase the chances of the aristocrat’s success in both politics and business. This jockeying for position very much characterized the scene at Rome in the waning days of the Roman Republic, and the Otricoli head is a reminder that one’s public image played a major role in what was a turbulent time in Roman history.

The Early Empire

The Roman Republic transformed into an Empire, with a somewhat mythologized and idealized emperor. Today, politicians think very carefully about how they will be photographed. Think about all the campaign commercials and print ads we are bombarded with every election season. These images tell us a lot about the candidates, including what they stand for and what agendas they are promoting. Similarly, Roman art was closely intertwined with politics and propaganda. This is especially true with portraits of Augustus, the first emperor of the Roman Empire; Augustus invoked the power of imagery to communicate his ideology.

One of Augustus’ most famous portraits is the so-called Augustus of Prima Porta of 20 BCE (the sculpture gets its name from the town in Italy where it was found in 1863). At first glance, this statue might appear to simply resemble a portrait of Augustus as an orator and general, but this sculpture also communicates a good deal about the emperor’s power and ideology. In fact, in this portrait, Augustus shows himself as a great military victor and a staunch supporter of Roman religion. The statue also foretells the 200 year period of peace that Augustus initiated, called the Pax Romana.

The Painted Garden of the Villa of Livia

The control of his personal image was only one way in which the rulers of the Roman Empire used art to control the perception of reality. Wall paintings were also used to bend and blur the lines between what is true and what is depicted.

Questions to Consider

- How has the artist of this work blurred the lines between image and reality? What elements of the work contribute to this effect?

- How does the naturalism (or verism) of this work relate to the styles of works from the Republican period?

It's a hot day in Rome, but the ancient Romans had figured out how to stay cool.

They did. We're in a room that reconstructs a room in the villa of Livia. Livia was the wife of the emperor, Augustus. There was a lovely summer house, a resort, of sorts. And in the villa, there was one room that was partially underground, dug into the rock.

Which meant they would stay much cooler in the summer.

And we can really appreciate that today.

But the sense of coolness would come not only from the actual temperature, but also from the decoration.

From the very cool colors that this room is painted in, what the artist did was paint an amazing illusion of a landscape, a garden, as though the walls were not walls at all, but views out beyond a fence, beyond a wall, with trees and bushes and fruits and plants and birds.

It's as if the walls have literally dissolved, and this is the great example of the second style of Roman wall painting.

The first style was characterized by an attempt to recreate in paint and stucco the marble walls that we've decorated Greek palaces.

A kind of faux marble, a kind of trompe l'oeil.

Exactly. Now here, instead of the illusion of marble, the artist has created an illusion of nature.

And it's nature that spreads out all around us. And it's not a menacing nature. It's a beautiful, cultivated nature. It's full of playful birds. There's fruit in the trees. There are blossoms everywhere.

And there's light. The artist has used atmospheric perspective so that the trees and the leaves that are closest to us are rendered more crisply than the vegetation in the background.

The only real architecture that's represented is, as you mentioned, a straw fence, perhaps, within something that looks a little bit more substantial, in a kind of pink-gray. The artist has used that outer wall in order to create a subtle rendering of perspective. And you can see that, as the wall reaches out in a couple of places to enclose trees that are just at the border.

So we see poppies and roses and irises and pomegranates and—

Quince.

So there's a real sense of variety in the plants, in the flowers, in the fruit, in the types of birds that we see, in the positions of the birds—some with their wings stretched back, some sitting quietly, some in the sky. There's a real search for the variety of nature. My favorite part is on this one tree that is framed by that pinkish-gray wall. The branches move in exactly the haphazard way that a tree grows. And then there are places where we see light on the leaves and branches and other places where the leaves are in shadow.

It seems as if, actually, there's a breeze that's come up, and it's blown some of those leaves over so that we're seeing the more silvery underside. And then we get the darker shadows of the tops of the leaves. So there's this real sense of the momentary, and of this being a breezy, beautiful day.

Yeah, you can almost hear the leaves rustle in the wind.

I think my favorite plant is probably the acanthus that grows up around a pine on one of the short sides of the room. And probably the other element that I find most interesting is that in this open-air space, there is perched precariously on that outer wall, a bird cage. Now, throughout this entire room, there are paintings of birds that are free and flying through the open sky. But here we have a bird in a cage. And it reminds me, as I stand in this room, that although these walls have dissolved, I'm still inside.

The plant species depicted include umbrella pine, oak, red fir, quince, pomegranate, myrtle, oleander, date palm, strawberry, laurel, viburnum, holm oak, boxwood, cypress, ivy, acanthus, rose, poppy, chrysanthemum, chamomile, fern, violet, and iris.

Another example of exquisite wall paintings in Ancient Rome comes from the Villa of Publius Fannius Synistor in Boscoreale Italy. Buried by a massive eruption of Mount Vesuvius, it features some of the highest quality Roman wall paintings of the period.

The Middle Empire

As the Empire expanded, the image of the emperor necessarily changed as well. During the height of the Empire, the emperor shed his mythological connections in favor of a military and civic character. In ancient Rome, equestrian statues of emperors would not have been uncommon sights in the city—late antique sources suggest that at least 22 of these “great horses” (equi magni) were to be seen—as they were official devices for honoring the emperor for singular military and civic achievements. The statues themselves were, in turn, copied in other media, including coins, for even wider distribution.

The Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius

Few examples of these equestrian statues survive from antiquity, however, making the Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius a singular artifact of Roman antiquity, one that has borne quiet witness to the ebb and flow of the city of Rome for nearly 1,900 years. A gilded bronze monument of the 170s CE that was originally dedicated to the emperor Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus, referred to commonly as Marcus Aurelius. The statue is an important object not only for the study of official Roman portraiture but also for the consideration of monumental dedications.

Tier 1: Content—Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius

Like all artwork, the content of this work contains elements worth exploring. As you consider this work, refer to the elements of art listed in Tier 1: Content.

This work uses line, form, and pictorial space to communicate a specific message about the emperor to the viewer.

The statue is an over-life-size depiction of the emperor elegantly mounted atop his horse while participating in a public ritual or ceremony; the statue stands approximately 4.24 meters tall. A gilded bronze statue, the piece was originally cast using the lost-wax technique, with horse and rider cast in multiple pieces and then soldered together after casting.

The emperor’s horse is a magnificent example of dynamism captured in the sculptural medium. The horse, caught in motion, raises its right foreleg at the knee while planting its left foreleg on the ground, its motion checked by the application of reins, which the emperor originally held in his left hand. The horse’s body—in particular its musculature—has been modeled very carefully by the artist, resulting in a powerful rendering. In keeping with the motion of the horse’s body, its head turns to its right, with its mouth opened slightly. The horse wears a harness, some elements of which have not survived. The horse is saddled with a Persian-style saddlecloth of several layers, as opposed to a rigid saddle. It should be noted that the horse is an important and expressive element of the overall composition.

The horseman sits astride the steed, with his left hand guiding the reins and his right arm raised to shoulder level, the hand outstretched. He is carefully composed by the artist and depicts a figure that is simultaneously dynamic and a bit passive and removed, by virtue of his facial expression. The locks of hair are curly and compact and distributed evenly; the beard is also curly, covering the cheeks and upper lip, and is worn longer at the chin. The pose of the body shows the rider’s head turned slightly to his right, in the direction of his outstretched right arm. The left hand originally held the reins (no longer preserved) between the index and middle fingers, with the palm facing upwards. Scholars continue to debate whether he originally held some attached figure or object in the palm of the left hand; possible suggestions have included a scepter, a globe, or a statue of victory—but there is no clear indication of any attachment point for such an object. On the left hand, the rider does wear the senatorial ring.

The rider is clad in civic garb, including a short-sleeved tunic that is gathered at the waist by a knotted belt (cingulum). Over the tunic, the rider wears a cloak (paludamentum) that is clasped at the right shoulder. On his feet, Marcus Aurelius wears the senatorial boots of the patrician class, known as calcei patricii.

We're in the Capitoline Museums in Rome, looking at the equestrian sculpture of the emperor Marcus Aurelius. We're not exactly sure of the date, but it's sometime around 176 or 180 CE.

It's in a new space because it was suffering some conservation problems and so had to be removed from the Campidoglio, where Michelangelo had put it.

And actually, that's an important point, because we don't know where it originally was in Rome.

No. What's really important is that this is the only equestrian sculpture of this size to survive from antiquity.

And we know that there had been dozens of them in Rome.

They were created to celebrate the triumphal return of an emperor.

There's so much authority as a result of him on horseback, clearly ruling. His left arm is lightly holding the reins—or would have been lightly holding the reins of the horse. The right hand protrudes out.

Addressing the troops or addressing the citizens of Rome.

There's a sense of confidence in his posture and, of course, in the scale.

It is enormous. This survived because it was thought to have represented Constantine, the emperor who made Christianity legal in the Roman Empire. And so this wasn't melted down for its bronze the way that almost all other equestrian sculptures were.

This could have ended up as a cannon. That's right.

So we're lucky it survived. And it had an enormous influence in the Renaissance for artists, beginning with Donatello and Leonardo da Vinci. And of course, also the ability to cast something this size in bronze had also been lost.

And it just shows how accomplished the ancient Romans were, both in their handling of the material, but also in the representation, the real understanding of the body, of its musculature.

And of the anatomy of the horse, striding forward. It's so animated and lifelike.

The folds of the neck as his head pushes downward.

And the folds of the drapery that Marcus Aurelius is wearing, how it comes down and drapes over his leg and the back of the horse.

There's also something really wonderfully momentary and also, at the same time, I think, very timeless here. The horse is striding, his arm is raised, but there's a wonderful sense of balance. The horse is in motion. He's pulling to the right.

He had in his left hand the reins, so there's a tension in that he sort of seems to be pulling back. And the horse pulls its head back a little bit. At the same time, the right side of his body seems to be moving forward.

And leaning to the right.

There's a kind of animation throughout.

There's also this unity between this incredibly powerful animal and Marcus Aurelius.

Right

He's in full control of the horse.

Yes.

And I think that that's the point.

And even kind of moving forward while pulling the horse back slightly.

With his body.

Like he's holding it back.

And you're right, his left hand is holding the reins, but it's a light touch even though he's in command of this incredibly powerful animal.

Yes. Is it me or does he seem a little too big for the horse? Do you know if this was cast in one piece?

It would have been cast in individual pieces. And then it would have been assembled. And then the bronze would have been worked so as to erase the seams.

And so this commemorating of a great man and his great deeds was an important idea in the Renaissance with the flowering of humanism, this recognition of the achievement of an individual, the representation of that individual in a portrait. These were things that had been lost in the Middle Ages.

This interest in representation, both of his authority, of his position in society, but also the ability to render the body, and then the interest in rendering. All of those things come together in the Renaissance again, having originally come together, of course, in the classical world.

The Late Empire

As the Roman Empire and the power of the emperor grew, so did the challenges. The imperial system of the Roman Empire depended heavily on the personality and standing of the emperor himself. The reigns of weak or unpopular emperors often ended in bloodshed in Rome and chaos throughout the empire. In the third century CE, the very existence of the empire was threatened by a combination of economic crisis, weak and short-lived emperors and usurpers (and the violent civil wars between their rival supporting armies), and massive barbarian penetration into Roman territory.

Relative stability was reestablished in the fourth century CE, through the emperor Diocletian’s division of the empire. The empire was divided into eastern and western halves and then into more easily administered units. Although some later emperors, such as Constantine, ruled the whole empire, the division between East and West became more marked as time passed. Financial pressures, urban decline, underpaid troops, and consequently overstretched frontiers—all of these finally caused the collapse of the Western Empire under waves of barbarian incursions in the early fifth century CE. The last western emperor, Romulus Augustus, was deposed in 476 CE, though the empire in the east, centered on Byzantium (Constantinople), continued until the 15th century.

During this period, the image of the emperors changed as well. With the split of the Empire, Diocletian divided the responsibilities of rule as well. Ultimately, four individuals carried this responsibility together, two emperors and two co-emperors, one of each for each half of the Empire. Thus the images of these emperors made a decided shift.

In the Portrait of the Four Tetrarchs, captured from Constantinople during one of the Crusades, we get a glimpse of this new style of portraiture that reflects the history of its time.