Chapter 4: Ancient Greece

Ancient Greek art is divided into five artistic periods; the geometric, Orientalizing, archaic, classical, and the Hellenistic. The art and architecture of Ancient Rome was heavily influenced by the Greek classical and Hellenistic periods. The ancient Greek belief that man is the measure of all things and capable of governing themselves led to the development of democracy and inspired their idealized depictions of the human body. Ancient Greek architecture is known for its emphasis on balance, order, and harmony, and its sense of timelessness has resulted in the style being imitated throughout history.

The Geometric and Orientalizing Periods

Following the collapse of the Mycenaean citadels of the late Bronze Age, the Greek mainland was traditionally thought to have entered a “dark age” that lasted from ca. 1100 until ca. 800 BCE. Not only did the complex socio-cultural system of the Mycenaeans disappear, but also its numerous achievements (e.g., metalworking, large-scale construction, writing). Nevertheless, some traditions persisted between these cultures, such as narrative elements in vase painting with decorative patterns that completely fill the surface, a stylistic trait of the Geometric Period. In the Orientalizing Period, this style continues but with more nuanced figural forms and intelligible illustrations, alongside Near Eastern motifs and animal processions.

To produce the characteristic red and black colors found on vases, Greek craftsmen used liquid clay as paint (termed “slip”) and perfected a complicated three-stage firing process. Not only did the pots have to be stacked in the kiln in a specific manner, but the conditions inside had to be precise. First, the temperature was stoked to about 800° centigrade and vents allowed for an oxidizing environment. At this point, the entire vase turned red in color. Next, by sealing the vents and increasing the temperature to around 900–950° centigrade, everything turned black and the areas painted with the slip vitrified (transformed into a glassy substance). Finally, in the last stage, the vents were reopened and oxidizing conditions returned inside the kiln. At this point, the unpainted zones of the vessel became red again while the vitrified slip (the painted areas) retained a glossy black hue. Through the introduction and removal of oxygen in the kiln and, simultaneously, the increase and decrease in temperature, the slip transformed into a glossy black color.

Briefly, ancient Greek vases display several painting techniques, and these are often period-specific. During the Geometric and Orientalizing periods (900–600 BCE), painters employed compasses to trace perfect circles and used silhouette and outline methods to delineate shapes and figures.

Around 625–600 BCE, Athens adopted the black-figure technique (i.e., dark-colored figures on a light background with incised detail). Originating in Corinth almost a century earlier, black-figure uses the silhouette manner in conjunction with added color and incision. Incision involves the removal of slip with a sharp instrument, and perhaps its most masterful application can be found on an amphora by Exekias (below). Often described as Achilles and Ajax playing a game, the seated warriors lean towards the center of the scene and are clothed in garments that feature intricate incised patterning. In addition to displaying more realistically defined figures, black-figure painters took care to differentiate gender with color: women were painted with added white; men remained black.

The red-figure technique was invented in Athens around 525–520 BCE and is the inverse of black-figure (below). Here light-colored figures are set against a dark background. Using added color and a brush to paint in details, red-figure painters watered down or thickened the slip in order to create different effects.

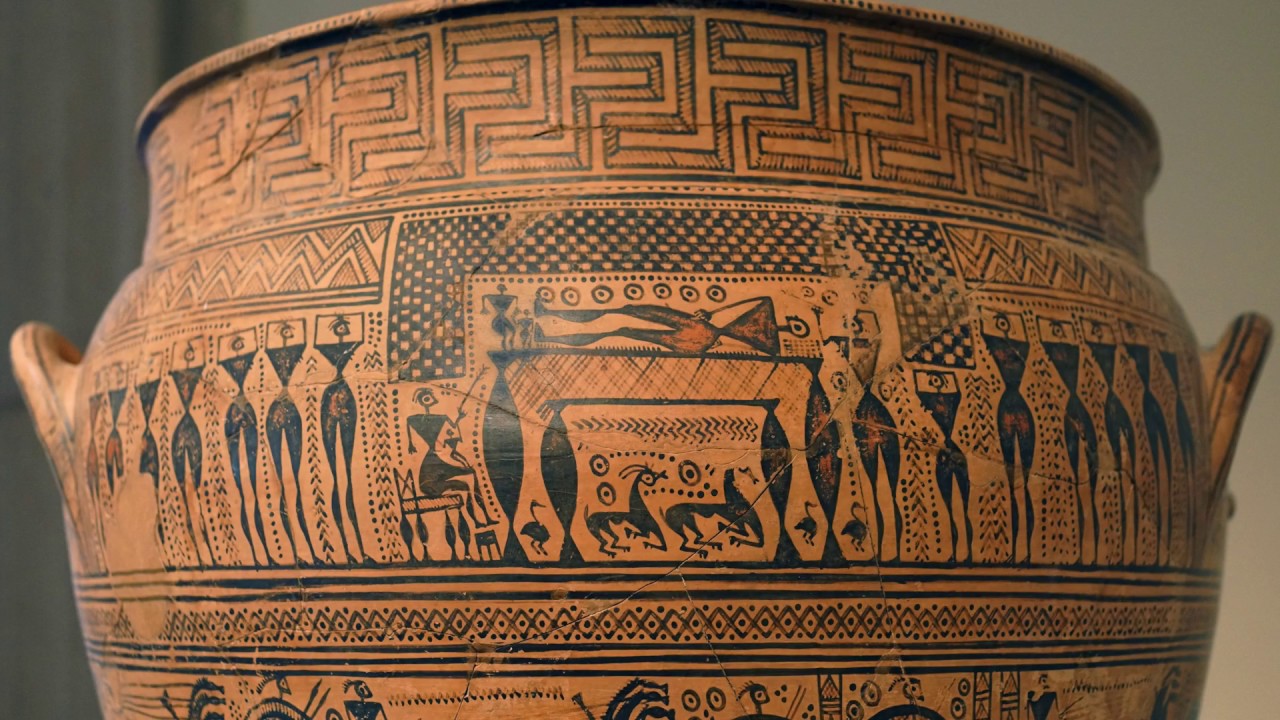

Terracotta Krater from the Dipylon Cemetery

From the geometric period of Ancient Greece, this terracotta krater marked a grave and depicts a mournful scene that is appropriate for this setting.

Questions to Consider

- How does the artist of this work use the elements of art to communicate its emotional content?

- How might the work be different if the abstract designs were removed?

We are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art looking at a gigantic clay pot.

This is from Ancient Greece, long before the classical period.

The shape of this vase makes it a krater, and it was found at the Dipylon cemetery in Athens.

Normally when we think about ancient Greek vases, we think about containers for wine or liquids, but this ceramic pot had a very different purpose. This was made to mark a gravesite.

We often think of headstones to mark a gravesite, but the Greeks used ceramic vessels. Somebody was buried underneath it.

And, in fact, the bottom of this vase is open, and it’s possible that liquid was poured in the top as an offering for the deceased, or it’s possible it was just used to drain off rainwater.

But what makes this vase so important, so extraordinary, is its decoration.

It is covered, every inch of this, with decoration, and that decoration is divided in two bands or registers.

This particular vase comes from an early period in Greek history, and the style that is associated with is geometric because the surface is covered with geometric motifs. You see diamonds and triangles and circles and meanders.

We also see broad areas of black paint and striped areas that form the base.

And this pot has pictorial bands, which we call friezes, and in them, and this is a little bit unusual for the geometric period, we see human figures, and we see animals, and the pictures remind us that this is funerary.

The large central scene along the top register shows us a figure on a bier, a dead figure who’s being mourned, and the figures on either side of him, the female figures, have raised their arms in a gesture of grief.

And some art historians have interpreted the decorative lines on either side of the figures as a reference to tears.

And it’s also possible that the checkboard pattern that’s above the deceased figure represents his funerary shroud, but lifted so that we can see the body.

I love how the human forms are nearly as abstract as geometric motifs that fill the rest of the vase. The torsos are nearly perfect triangles, the heads, which are shown in profile, are basically circles with eyes in the center.

And the legs are lozenge-shaped, as are the legs of the table that the deceased figure is on, or the legs of the chair. When you walk up to this you might not even notice at first that you were looking at a narrative scene, that you were looking at human figures.

The band below shows a procession and its military in nature. We see chariots; we see horsemen; we see soldiers with shields and spears and swords. In fact, the bodies are reduced to the form of ancient Greek shields.

And the horses were given three horses at a time, and appropriately, there are six legs in the front and six legs in the back, but there is no sense at all the space the three horses would occupy.

Everything on the surface of this vase fills flat. There’s no pictorial depth, there’s no interest in illusionism in that sense.

Not at all. And yet, in the scene of a funeral, with perhaps his wife and child beside him, and mourners around him, we still get a really palpable sense of sadness, of death here.

The pot was decorated with a material that is called slip, very fine particles of clay, that are suspended in a liquid, and then painted onto the surface. The Greeks at this point didn’t use kilns that were hot enough to create the glassy surface that we take for granted in modern ceramics that we call glaze, and this kind of ceramic is known as slipware.

And this would have been turned on a wheel.

So from far away in the cemetery, your eyes might be drawn to this pot, and therefore to the man that this pot commemorates.

The Archaic Period

While Greek artisans continued to develop their individual crafts, storytelling ability, and more realistic portrayals of human figures throughout the Archaic Period, the city of Athens witnessed the rise and fall of tyrants and the introduction of democracy by the statesman Kleisthenes in the years 508 and 507 BCE.

Visually, the period is known for large-scale marble kouros (male youth) and kore (female youth) sculptures. Showing the influence of ancient Egyptian sculpture, the kouros stands rigidly with both arms extended at the side and one leg advanced. Frequently employed as grave markers, these sculptural types displayed unabashed nudity, highlighting their complicated hairstyles and abstracted musculature. The kore, on the other hand, was never nude. Not only was her form draped in layers of fabric, but she was also ornamented with jewelry and adorned with a crown. Though some have been discovered in funerary contexts, a vast majority were found on the Acropolis in Athens. Ritualistically buried following the desecration of this sanctuary by the Persians in 480 and 479 BCE., dozens of korai were unearthed alongside other dedicatory artifacts. While the identities of these figures have been hotly debated in recent times, most agree that they were originally intended as votive offerings to the goddess Athena.

The Classical Period

Though experimentation in realistic movement began before the end of the archaic period, it was not until the classical period that two- and three-dimensional forms achieved proportions and postures that were naturalistic. The early classical period (480/479–450 BCE) was a period of transition when some sculptural work displayed archaizing holdovers. During the “High Classical Period” (450–400 BCE), there was great artistic success: from the innovative structures on the Acropolis to Polykleitos’ visual and cerebral manifestation of idealization in his sculpture of a young man holding a spear, the Doryphoros or “Canon.” Concurrently, however, Athens, Sparta, and their mutual allies were embroiled in the Peloponnesian War, a bitter conflict that lasted for several decades and ended in 404 BCE. Despite continued military activity throughout the late classical period (400–323 BCE), artistic production and development continued apace. In addition to a new figural aesthetic in the fourth century known for its longer torsos and limbs and smaller heads (for example, the Apoxyomenos), the first female nude was produced, known as the Aphrodite of Knidos, ca. 350 BCE.

One significant feature of statuary at this time involved the naturalistic representation of the human body. Rather than the stiff, lifeless poses employed in the Archaic Period, artisans of the classical period developed and mastered contrapposto, a stance that replicates the artisan's attention to the anatomy and behavior of the human form. In this form, the weight of the body is shifted to one leg, resulting in the compensatory angling of the hips and shoulders. Though perhaps not immediately apparent, this development was an enormous advancement in skill by which the artisan produces a work weighing several thousand pounds that appears to occupy space as gracefully as the human body.

Let's explore a work from this period in greater detail.

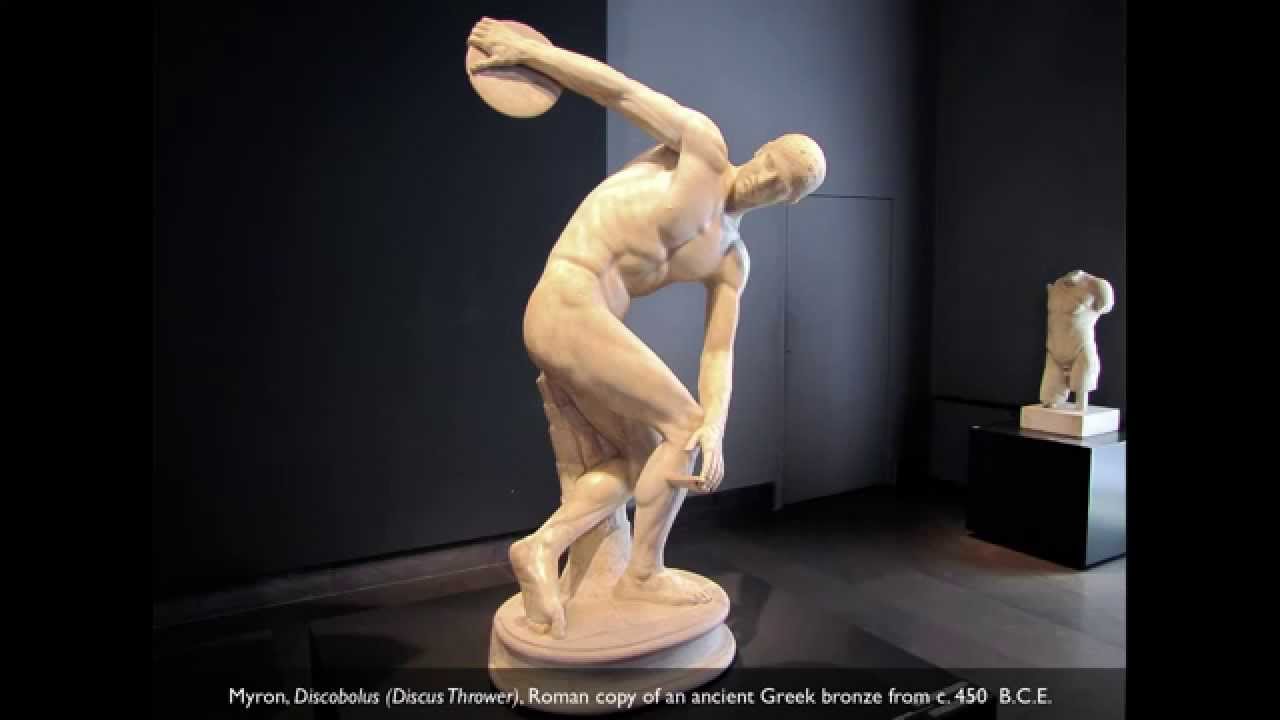

The Discobolus

Questions to Consider

- What artistic elements does the artisan employ to produce this lifelike or naturalistic sculpture?

- How does this artwork reflect the interests of the classical period?

Ancient Greek sculptures, bronze or marble, are frozen. But that doesn't mean that the ancient Greeks didn't want to convey movement.

In this case, movement that you couldn't even see with the naked eye.

What we're looking at is a sculpture by an artist whose name is Myron. We've lost his original, but we have a later Roman marble copy of the "Discus Thrower."

The original was in bronze from the fifth century BCE.

And what we're looking at is one of many Roman copies. In fact, there's one next to the other in this museum, a testament to how popular these were among the Romans.

The sculpture shows a man who is at that moment where his body is fully wound. Look at the way that his right leg is bearing the weight of his body. His left leg, the toes are bent under, dragging slightly, and he's about to throw that discus. This is a moment of tremendous tension, but it's also this moment stasis, of stillness, right before the action.

Athletes and art historians have debated whether this is even an actual pose that the discus thrower takes in the process.

It's so interesting, because when we think back about the history of the Greek figure, we think first of the Archaic Kouros, who is so stiff and so stylized. And then we have the tremendous breakthroughs of people like Polykleitos who developed an understanding of the body and showed in a contrapposto. But here we have something that's so dynamic and so complex, I mean just look at the arc of the shoulders and the arms, and the way that they reverse the arc of the twist of the hips.

That is the overriding concern of Myron, the sculptor, to capture the aesthetic qualities here. The sense of balance and harmony, and the beauty in the proportions of the body.

There is kind of anti-realism here, for all of its careful naturalism. There is no real strain within the body. It is absolutely at rest, and ideal, even in this extreme pose.

If you think about a figure from much later, but in a similar pose of movement, of athletic energy, like Bernini's "David."

Well, that's got all this torsion, absolutely.

That figure expresses all of the physical power in the face. He's clenching his teeth, right?

That's true. And his brow is really knit forward. But here, the face is absolutely serene. And it reminds me of the consistency with which the Greeks always maintain their nobility, even in battle, even in terrible situations with monsters. And here, even at this moment when he's about to release the discus.

Right, that nobility, that calm in the face, is a sign of a nobility of the human being.

Well, this is a sport, and the man is naked, which is what the Greeks did. But there was a real logic there. Why would you cover up the beauty of the body in sport, which is, of course, a celebration of what the human body can achieve? This is really a way to remind ourselves of the Greeks' concern with the potential of humanity, the potential of the mind, and the potential of the body.

Taking that extra step to become even more ideal, more heroic, more noble, than even the finest athlete.

It is a perfect form.

The Hellenistic Period

Following the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, the Greeks and their influence stretched as far east as modern India. While some pieces intentionally mimicked the Classical style of the previous period, other artists were more interested in capturing motion and emotion in addition to virtuosic naturalism. In this period, artists embellished their works with features that dazzle the senses, from flowing drapery to intense emotional facial expressions, to the point that the viewer may forget the artistic medium itself (such as marble or bronze).

The Seated Boxer is a dazzling example of this form of expression. One of the few bronze castings to survive from this period, this work depicts an exquisite display of attention toward naturalism. Not only does the artist capture an accurate depiction of the human form but also a collection of less idealistic features including a swollen ear (often called cauliflower ear, a common injury for boxers), cuts and scrapes, and even the suggestion of blood through the mixing of clay into the bronze at the time of casting.

Nike of Samothrace

One of the most revered artworks of Hellenistic Greek art, the Nike, as it stands today in the Louvre, has been partially restored. While it is now plain white marble, the statue, like all ancient Greek and Roman marble sculptures, would have originally been brightly painted, and traces of pigment have been found on the statue. The right wing is a modern replica. Surviving fragments indicate that the right wing would have risen higher than the left wing and slanted upward. The missing feet, arms, and head have not been restored, giving the statue its now iconic form.

Tier 1: Content—Nike of Samothrace

Like all artwork, the content of this work contains elements worth exploring. As you consider this work, refer to the elements of art listed in Tier 1: Content.

This work uses composition, texture, and pictorial space in novel ways. The sculptural group consists of two parts, a large ship’s bow made of grey marble and a free-standing white marble statue with the overall composition rising more than eighteen feet (Nike alone is nine feet tall). The flying personification of victory (nikē in Greek means victory) alights on top of the ship, announcing a naval triumph. Her wings stretch dramatically behind her. A forceful wind blows her drapery across her body, gathering it in heavy folds between her legs, around her waist, and streaming behind her, conveying a vivid illusion of movement. Thin and gauzy across her breasts, abdomen, and legs, this same drapery reveals her body underneath the clothing, enhancing the vision of the human form.

Similar to other Hellenistic artworks such as the Laocöon and the Great Altar at Pergamon, the Nike is extraordinarily dramatic in composition and style. It is intended to be viewed from multiple angles, encouraging the viewer to move around the statue, and through this interaction engage with the artwork physically and emotionally.

Nike’s wings are a mastery of marble construction. Marble is a heavy material and compositions that included large, protruding, unsupported elements such as the wings were rarely seen in earlier Greek sculpture. The now-unknown artist(s) of the Nike of Samothrace solved this problem by creating slots on Nike’s back into which the wings were inserted, and designing the wings with a downward slope so that the weight of the wings rested primarily against the body and did not need an external support.

We are standing in the Louvre, looking at the very famous Nike of Samothrace. Now a Nike personifies victory.

And was the goddess of victory as well. This sculpture is 18 feet tall if you include the ship that she stands on. And it's placed at the top of one of the grand staircases, so it’s incredibly dramatic.

She was found in pieces. She wasn’t found whole the way that we see her today, and she’s been reconstructed. The pieces that were missing have been filled in, and he was recently restored.

Originally, this was placed in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods on the Island of Samothrace in the northeastern Aegean Sea. But we should say that we have very little information about this particular cult. What we do have is a magnificent sculpture. It was carved during the Hellenistic period. This is after the classical period, after Alexander the Great created one of the largest empires the world had known to that date. And it was a period when Greek art was extremely expressive. In fact, art historians often pair this sculpture in its style with a sculpture that we find on the great frieze at the Altar of Zeus at Pergamon.

In both cases, there’s a sense of energy, drama, and power. And although we can compare the drapery that clings in these complex folds to the body, to the sculptures on the earlier Parthenon, there’s so much more drama here.

I love the way in which the drape seems to be whipped by the wind. And It’s interesting to note that the way that this ship would have originally been oriented, it would have been facing towards the coast with the wind coming off the sea. And so, the actual wind on Samothrace would have functioned as a collaborator with the illusion of the sculpture.

Now Nike figures are not unusual in ancient Greek art. To me, what’s so special about this figure is the tension between the lower half of the body and the upper half. She’s clearly alighting landing on this ship, but with the lower part of the body, I feel that pull downward. But the upper part of her body seems to still be held aloft, and so her torso stretches up and twists slightly in the opposite direction of her legs. So, there’s this upward movement, but downward movement at the same time.

The sense of naturalism is so extraordinary that there seems to be nothing improbable about the wings attached to the shoulders of this figure. It just seems completely natural.

It used to be thought that perhaps this figure stood within a fountain, and perhaps was blowing a trumpet or offering a crown of victory, but we now think that her hand was simply outstretched. Either she was in an open sanctuary or a slightly enclosed sanctuary. I love the pinkish-white, almost golden color of the marble that she’s carved from, and the grayish color of the ship.

There’s a wonderful contrast between those two materials. Although she’s lost her head, and both of her arms, and other bits and pieces as well, we are so lucky to have this sculpture this intact.

Well think about all that’s been lost, that didn’t survive, and this incredible achievements of ancient Greek and specifically Hellenistic art.